The H.L. Hunley was the first submarine to ever sink an enemy ship in combat.

Sounds great and I guess it is, until you realize it was powered by eight dudes hand-cranking a propeller in the dark, like some haunted Civil War rowing machine. Cramped, hot, pitch black, and barely big enough to sit upright this thing was more iron tomb than anything.

In 1864, the Hunley pulled off what no one thought was possible. It crept up on the Union warship USS Housatonic off the coast of Charleston, planted a torpedo on a long spar mounted to its nose, and blew the ship out of the water.

Mission accomplished. First sub-to-ship kill in world history.

Would not be a Wacky Wednesday if it ended there.

The Hunley never came back. It sank too.

And here’s the wild part: this wasn’t the first time it happened. It was the third time the sub had killed everyone on board.

Once during testing.

Once during a training run with its inventor, Horace Hunley, on board.

And now, even after a successful combat mission.

Then the thing disappeared for over 130 years. No wreck, no clues just gone.

When they finally found it in the 1990s and brought it to the surface, what they found inside was pretty terrifying. No holes in the hull. No signs of flooding or damage. Just dead.

To this day, no one really knows how or why but it is thought that the spar torpedo used to sink the Housatonic was the culprit.

Whatever happened, it was fast and silent.

So yeah, the Hunley made history. But it also sank three times, killed 21 men, and vanished into legend for over a century.

Most cursed sub in history? Probably.

Image 1 (Actual Submarine): Courtesy of the Friends of the Hunley, www.hunley.org

Image 2 (Crew Model): Photo by Gerry Dincher, via Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons license https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hunley_model_cutaway.jpg

Content sources

Friends of the Hunley – www.hunley.org National Park Service – nps.gov

Smithsonian Magazine – The Hunley Submarine Mystery

Naval History & Heritage Command – history.navy.mil

Crew model photo by Gerry Dincher via Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 2.0

Illustration of Union and Confederate soldiers clashing at Pigeon’s Ranch during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, painted by Roy Andersen.

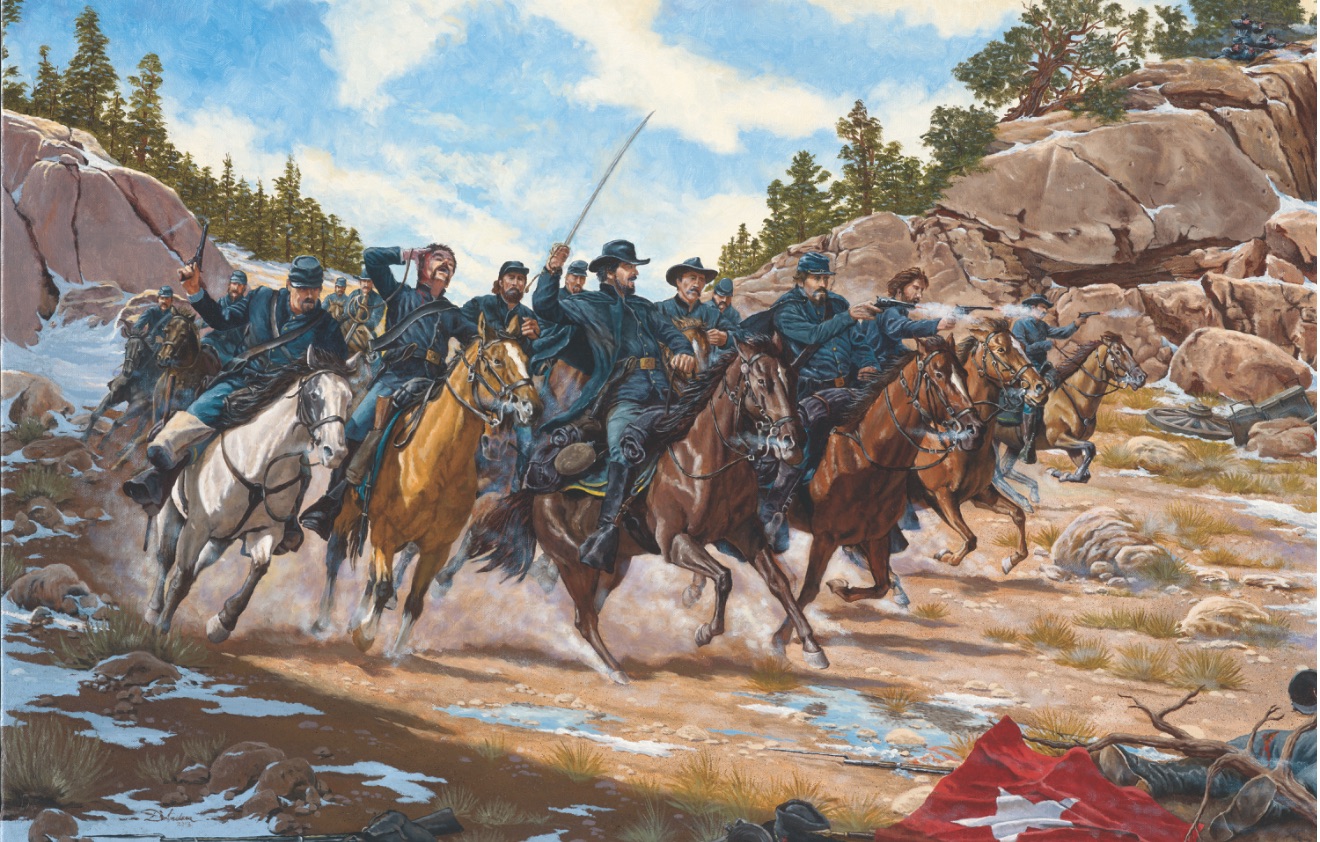

Illustration of Union and Confederate soldiers clashing at Pigeon’s Ranch during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, painted by Roy Andersen. Painting of the Union cavalry charge at Apache Canyon during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, March 1862, by Domenick D’Andrea.

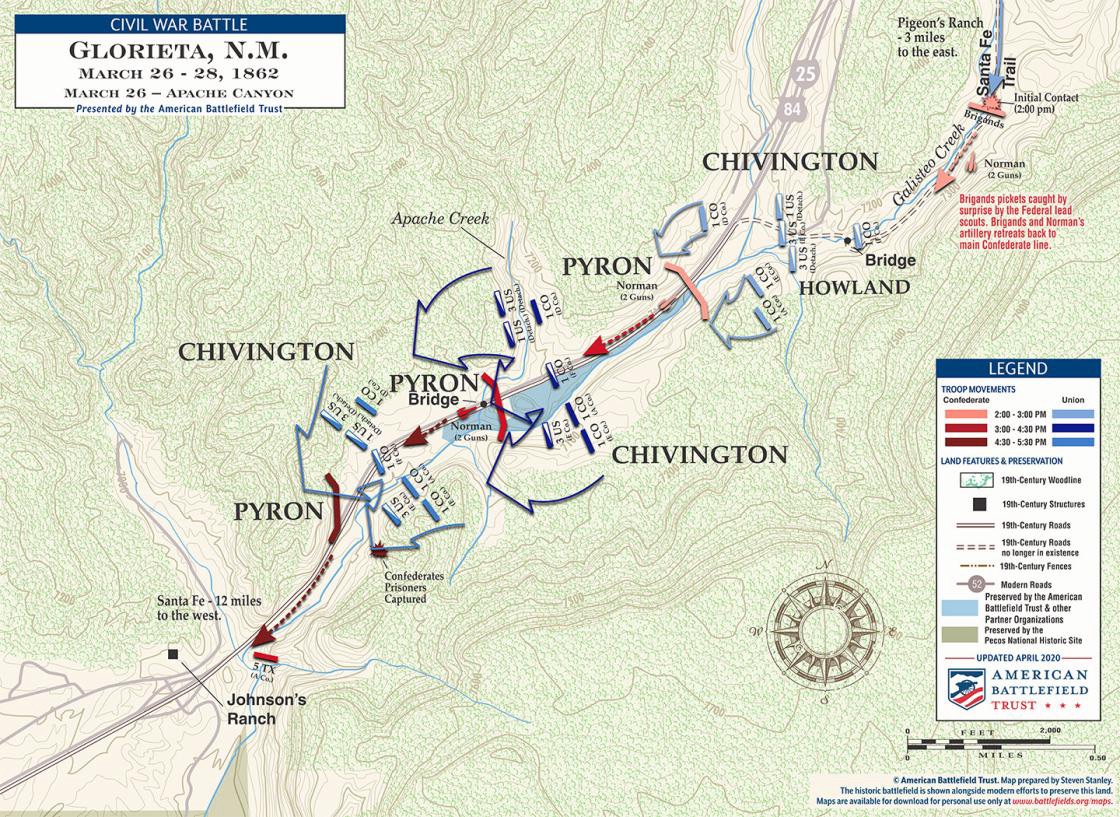

Painting of the Union cavalry charge at Apache Canyon during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, March 1862, by Domenick D’Andrea. Battle map showing Union and Confederate troop movements at Apache Canyon on March 26, 1862, during the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Battle map showing Union and Confederate troop movements at Apache Canyon on March 26, 1862, during the Battle of Glorieta Pass.  Civil War battle map showing troop positions at Pigeon’s Ranch on March 28, 1862, during the final day of the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Civil War battle map showing troop positions at Pigeon’s Ranch on March 28, 1862, during the final day of the Battle of Glorieta Pass.