If you ever drive through Tennessee, it feels calm and ordinary. A mix of neighborhoods, trees, and quiet roads. It’s weird to think that those same fields were anything but peaceful. In the final days of 1862 and the start of 1863, a small town became the site of one of the most brutal battles of the Civil War, known as the Battle of Stones River.

Setting the Stage

By late 1862, things were tense for both the Union and the Confederacy. General William Rosecrans had just taken over the Union’s Army of the Cumberland, and General Braxton Bragg was leading the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Both men were confident, but both were under a ton of pressure from both their presidents, although maybe not Bragg because Davis loved him, but regardless. Rosecrans needed a clear victory to hold Nashville. Bragg wanted redemption after earlier losses and a chance to prove the South could still hit hard.

They finally crossed paths outside Murfreesboro, a place divided by a cold, twisting river that soon ran red with blood.

The Battle Begins

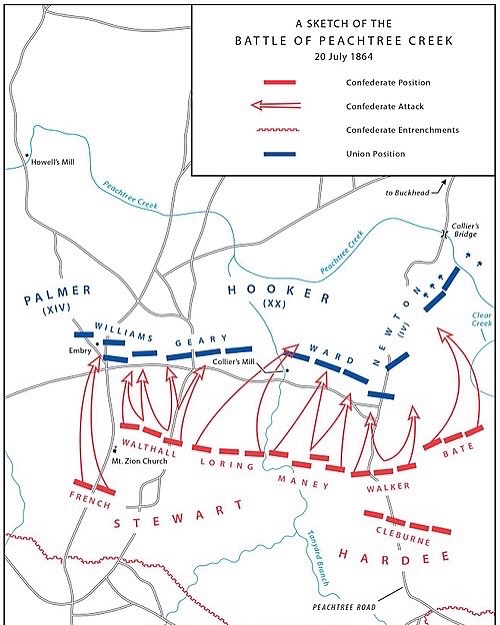

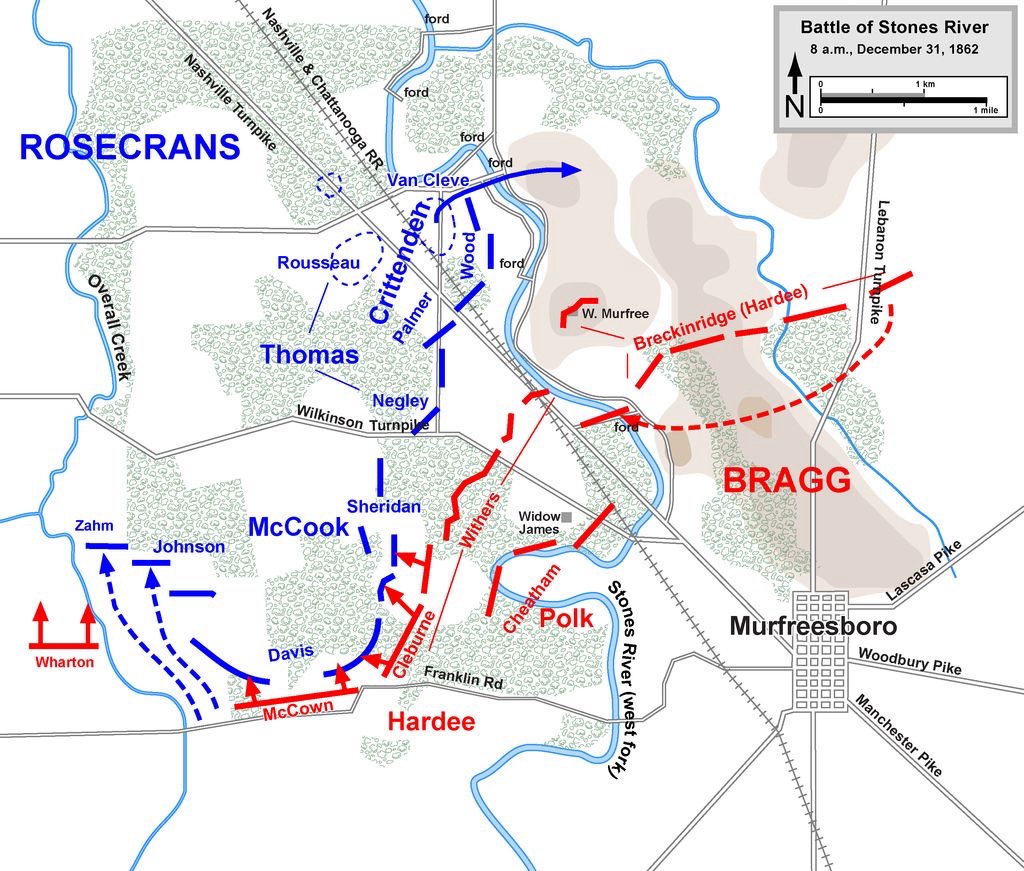

On December 31, Bragg went on the attack. He hit the Union right flank as hard as he could, and for a few hours it looked like the Confederates might pull it off. Union troops were pushed back again and again, fighting tooth and nail just to hold their ground. The noise must have been unbearable gunfire, cannon blasts, and the screams of the wounded.

Still, Rosecrans held firm. Covered in blood from a grazing wound, he rode along the front lines shouting orders and trying to keep his men from breaking. On January 2, the Confederates tried again, launching another attack across Stones River. It went horribly wrong. Union artillery tore them apart in minutes. Many of Bragg’s men were killed on the spot or swept away trying to retreat across the icy water.

By January 3, Bragg had no choice but to fall back. The Union army stayed where it was. Technically, it was a victory but a very costly one.

The Cost and Consequences

Out of about 81,000 soldiers who fought, over 23,000 were killed, wounded, or missing. That’s almost one out of every three men. Lincoln, desperate for good news, called it one of the most important Union victories of the war. “God bless you and all with you,” he wrote to Rosecrans. It was a small boost in a very dark winter for the North.

For the South, it was a painful loss. Tennessee had been a major stronghold, but after Stones River, the Union’s grip on the state only tightened. Bragg’s leadership was questioned, and his own officers started to turn against him. The cracks inside the Confederate command grew wider.