The “Gettysburg of the West”

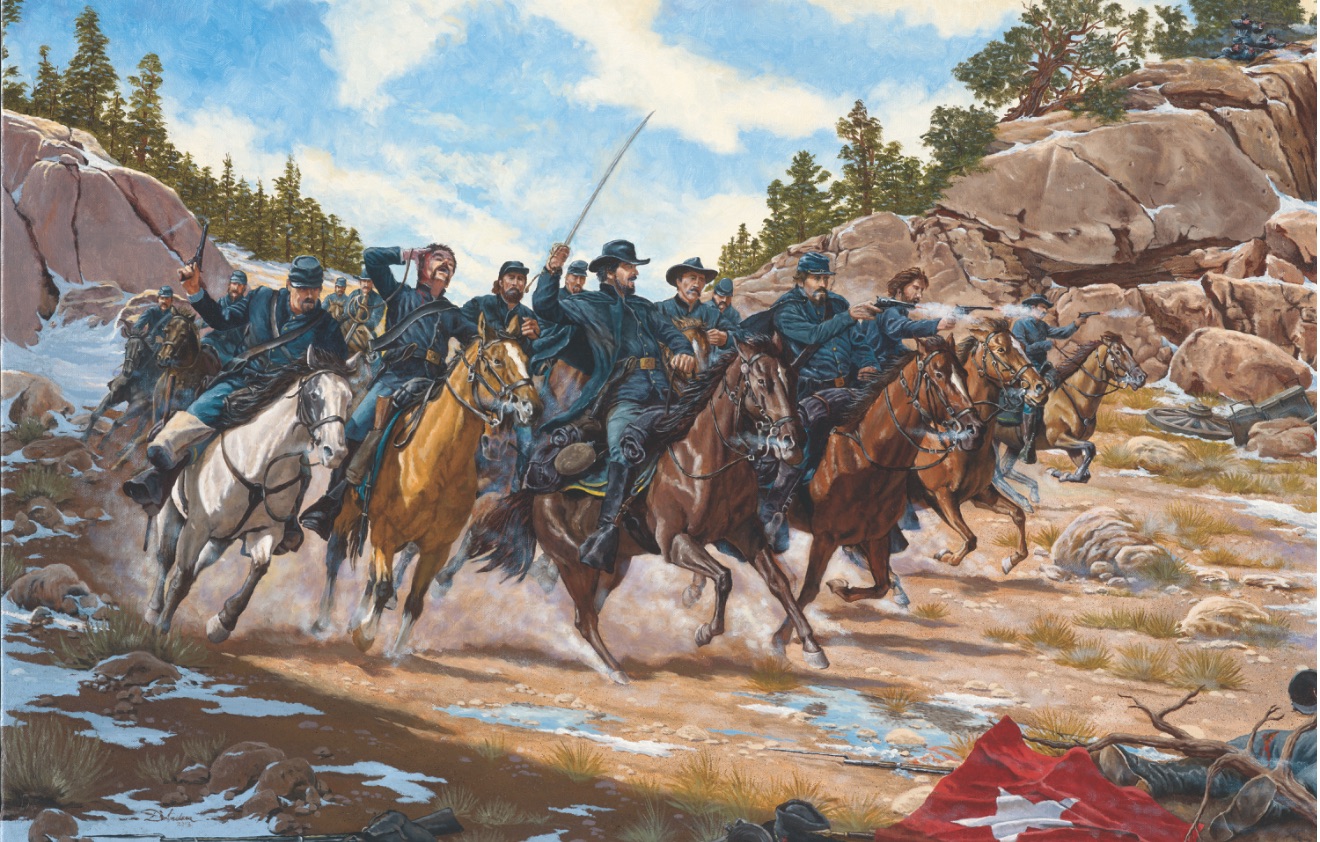

Illustration of Union and Confederate soldiers clashing at Pigeon’s Ranch during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, painted by Roy Andersen.

Illustration of Union and Confederate soldiers clashing at Pigeon’s Ranch during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, painted by Roy Andersen.When people think of the Civil War, they picture Virginia, Pennsylvania, maybe Tennessee, but not New Mexico. In the mountains of the Southwest, a battle played out that could’ve changed the course of the war in the West. It’s called the Battle of Glorieta Pass, and while it doesn’t get the attention of places like Gettysburg or Antietam, it was still a turning point in the fractured nation.

This was in March 1862. The Confederacy had the idea to sweep westward and take the gold fields in Colorado, eventually snagging California’s ports, and maybe even gain international recognition. They sent troops under General Sibley north from Texas, and they’d already taken Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Things were looking pretty good for them up to this point.

Then comes Glorieta Pass.

Painting of the Union cavalry charge at Apache Canyon during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, March 1862, by Domenick D’Andrea.

Painting of the Union cavalry charge at Apache Canyon during the Battle of Glorieta Pass, March 1862, by Domenick D’Andrea.This narrow, rugged pass in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains was basically the gateway to the rest of the West. Union troops, including a mix of regular soldiers and Colorado volunteers, moved in to stop the Confederate advance. What happened next was a three-day fight, March 26 to 28, that was brutal, confusing, and fought in freezing weather and rocky terrain.

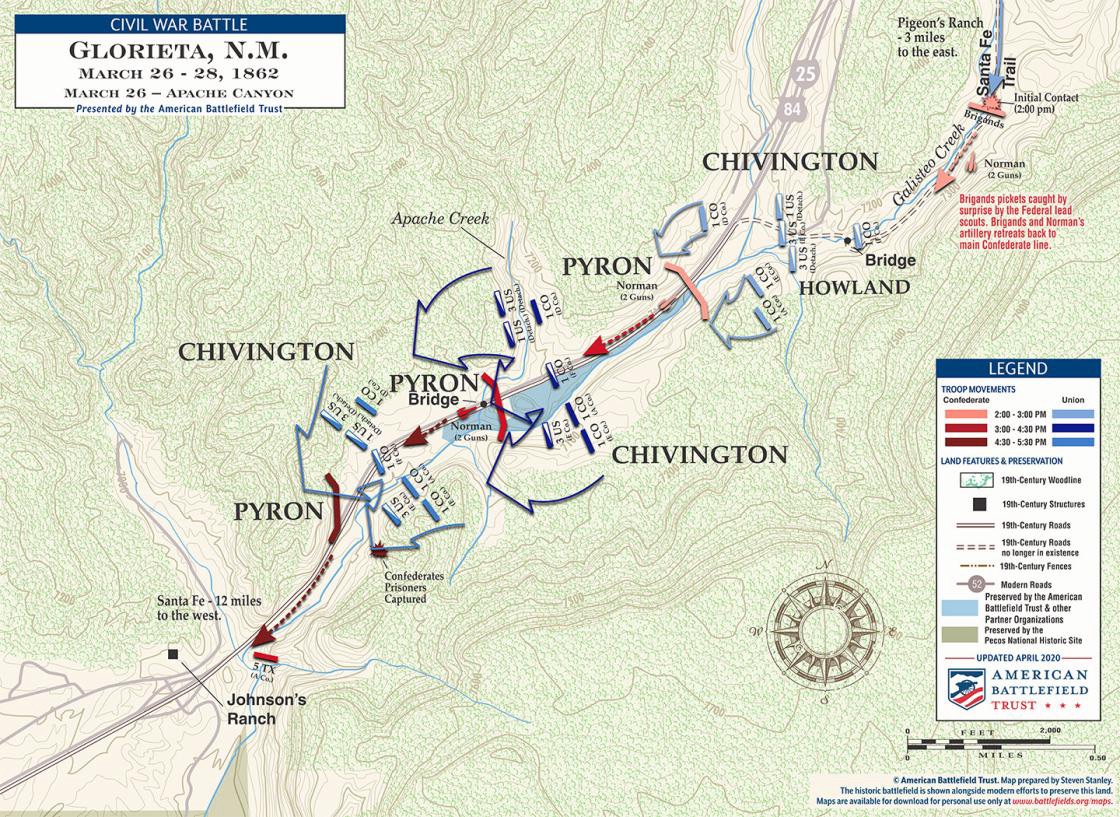

Battle map showing Union and Confederate troop movements at Apache Canyon on March 26, 1862, during the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Battle map showing Union and Confederate troop movements at Apache Canyon on March 26, 1862, during the Battle of Glorieta Pass. The actual fighting was fierce. At one point, hand-to-hand combat broke out in a narrow canyon. Both sides claimed small victories, but it was what happened off the battlefield that really decided things. A group of Union soldiers, led by Major John Chivington, snuck around and found the Confederate supply train. They destroyed it — wagons, food, ammo, everything. Just torched it all.

With no supplies and hundreds of miles from home, the Confederates had no choice but to retreat. Their whole campaign collapsed.

Civil War battle map showing troop positions at Pigeon’s Ranch on March 28, 1862, during the final day of the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Civil War battle map showing troop positions at Pigeon’s Ranch on March 28, 1862, during the final day of the Battle of Glorieta Pass. That’s why some folks call Glorieta Pass the “Gettysburg of the West.” It stopped the Confederate push. If they’d succeeded, who knows how the map of America might look today?

It’s a strange little battle; not huge in numbers, but huge in impact. And it’s a good reminder that the Civil War wasn’t just fought in the green fields of Virginia or along the Mississippi River. It reached the deserts, the mountains, and even the far corners of the frontier.

Sources & Further Reading

- National Park Service: Battle of Glorieta Pass

- American Battlefield Trust: The Battle of Glorieta

- Wikipedia: Battle of Glorieta Pass

Image Credits

- “Action at Apache Canyon” painting by Domenick D’Andrea – National Guard Heritage Series

- Map of the Fight for Apache Canyon (March 26, 1862) – American Battlefield Trust

- “Battle of Glorieta Pass at Pigeon’s Ranch” by Roy Andersen – Wikimedia Commons

- Map of the Fight for Pigeon’s Ranch (March 28, 1862) – American Battlefield Trust